On the Genealogy of Happiness

Happiness as good fortune, as virtue, and as pleasure; plus the origins of relativism [Premium post now free]

Before Socrates, the ancient Greeks thought that a good or happy life (eudaimonia) was almost entirely a matter of luck or good fortune. Eudaimonia literally translates to “good spirit,” from eu=good and daimon=demon/spirit. Daron MacMahon, author of Happiness: A History, writes, in a special edition of the journal Daedalus devoted to the topic of happiness:

“In colloquial terms, to be eudaimon was to be lucky, for in a world fraught with constant upheaval, uncertainty, and privation, to have a good spirit working on one’s behalf was […] the key to happiness.”

Life was so thoroughly ruled by precariousness and chance that a life earning a positive evaluation from oneself or others must be chalked up to the gods looking out for you.

While eudaimonia has been translated sometimes as “happiness,” it is important to remember that the pre-Socratic meaning of eudaimonia did not have the connotation of pleasure or pleasantness that the English word “happiness” often has today.

Against this world view, which Nietzsche rightly labeled “tragic,” ancient Greek philosophers, particularly Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, would argue that a life could be good or better if one lived virtuously and rationally, even though of course misfortunes could still befall one. As MacMahon says, these philosophers of the virtuous and examined life sought to…

“circumscribe the role of chance… to cow it into submission by virtue’s superior force.”

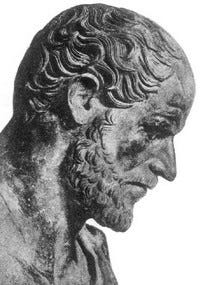

Aristotle gave bad luck its due, but tried to mitigate its effect on life with good habits, good reasoning, good friends, and the rest of his famous list of virtues, which includes: courage, as the mid-point between the vices of foolhardy and fear; confidence, the mid-point between the vices of rashness and shyness; magnanimity or greatness of spirit, the midway between the vices of vanity and smallness; candidness, midway between the vices of being brutally honest and condescendingly over-protective; modest, midway between boastful and self-deprecating; witty, midway between boorish and buffoonish; ambitious, midway between excessively prideful and lazy; spirited, midway between melancholy and boisterous; just (justice) or righteous indignation, midway between excessive anger and moral laxity and blindness.

After Aristotle, the ancient Stoics’ ethical theory attempted entirely to decouple good or bad luck from an eudaimon life. How? By locating happiness in our inner life, our reaction to misfortune, bad luck.

But the association of happiness and luck would persist and happiness would not take on the connotations of pleasantness at least until after the end of the Dark Ages in the Early Modern or Enlightenment period.

For instance, in early Middle English, and in Old Norse, happ meant chance, fortune, what happens in the world. I find that to be a fascinating connection between the English words happiness and happening.

In Middle High German, and still today, there is one and the same word for happiness and luck, namely Glück.

In Old French, heur (luck, chance) is the root of bonheur which is translated as happiness. (However, the Scottish and British enlightenment was conducted in English and, to me at least, it is very hard to hear the “happ” of “chance happening” when I hear the “happ” of “happiness,” in English. Glück makes it easier.)

The Stoics Cicero and Epictetus took the fight against the vagaries of life to its extreme logical conclusion, saying if one controlled one’s own mind and emotional reaction, one could be eudaimon in the middle of the worst luck and worst pain.

According to the Stoics,

“[h]appiness is a function of the will, not of external forces,”

writes MacMahon, expressing an idea echoed among nearly all my first-year college students.

We may think the Stoics take it too far, but the kernel is sound or represents well the thoughts of the Ancient era. “The classical view,” MacMahon writes, was that

“happiness and pain were by no means mutually exclusive.”

This goes two ways. You could be in lots of pain and still be eudaimon if you practiced Socrates’ or Aristotle’s virtues sufficiently well. And, going the other way, you could be ecstatic with pleasure and the absence of pain and still not be eudaimon if you happened to lack Socrates’ or Aristotle’s virtues. (It helps to think of “a happy life” rather than “happiness” when trying to grok a meaning of “eudaimonia/happiness” that includes as a necessary component the achievement of moral goodness.)

In his effort to try to push back against the tragedies of life and the role of random luck in the value or worth or goodness or fortunateness of a life, Aristotle offered a new definition of eudaimonia.

Aristotle’s ethical theory redefined eudaimonia as “rational activity of the soul that expresses virtue.”

Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle were not as concerned as we may think with whether or not the eudaimon—a.k.a., the virtuous and examined—life was a pleasant life, i.e., a life of pleasure.

What concern they do voice was born from a philosophical conviction about human motivation, namely that a person always acts (via their chosen means) towards an end they conceive of as good. Socrates took this idea so far as to say that no one ever does bad things intentionally; one does bad things only out of ignorance of the Good. If they knew the true Good, they would not have done the bad thing. And since everyone always acts toward an end they conceive of as good, then the thing we are calling bad must have been conceived by the wrongdoer at least in some sense as a good thing to do. Usually the wrongdoer does the bad act knowing others will call it bad, but as it benefits him, or as it will accrue to his good, he is going to do it anyway, which places the wrong doer’s minor pleasure over the perhaps considerable harm that bad act will inflict on the wrong doer’s victims. Performing that calculation incorrectly was what Socrates meant by ignorance of the (true) good.

Thus, Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle felt obligated (because of this theory of motivation) to argue that the hard work of living a virtuous life was in your interest, was good, and in some cases, was pleasant or a species of pleasure.

In the Christian age—from the period of late annuity, embodied in Augustine, through the middle ages embodied in Aquinas, and to the Enlightenment embodied in the American Founding Fathers—pleasure, virtue, and happiness get all tangled up.

The ancient and Hellenic inheritance in Europe included the idea that a good life was a virtuous life and that if you were not virtuous you could not be happy. Our modern ears have a hard time with that last one. We think that if someone gets pleasure out of unjustified murder and tells us that he is happy, then he is happy. But that kind of relativism about the Good, about pleasure, and about happiness was an unlikely thought in philosophy and in culture before the advent of relativism.

Yes, relativism was not always the self-evident truth my students and many others today take it to be. It has a history—a quite interesting history to my mind.

The relativism of today did not start to take shape at least until after the advent of religious pluralism, the origin of which traces back to end of the religious wars which had pitted Protestants against Catholics in the 1600s, such as the Thirty Years War. As John Rawls writes in a discussion of liberal pluralism,

“The ancient world did not know the clash between salvationist, creedal, and expansionist religions,”

… by which he means the transcendentally pitched, maximalist, monotheistic religion of Christianity. When Christianity was unified and one, there was no need for pluralism and no possibility of relativism. But then Christianity split into Protestants and Catholics, and there were two sets of evidently incompatible transcendentally important creeds, and the wars were especially horrific and uncompromising.

Because to compromise would be to “acquiesce in heresy about first things,” Rawls notes.

While the religious wars of the pre-modern period were undoubtedly still partly economic and partly religio-cultural, as all wars probably are, an aspect of their religious dimension was new and special. As Rawls says,

“This [new and special] element forced [there to be] either mortal conflict moderated only by circumstance and exhaustion, or equal liberty of conscience and freedom of thought.”

And so we get the first green sprouts of pluralism.

Rawls credits Hegel for seeing that the desire to end this internecine conflict allowed for the modern understanding of liberty of conscience, and freedom of thought (by which he means toleration, liberalism, pluralism, and letting bygones be bygones).

But close on the heels of the beginnings of pluralism came the beginnings of relativism and ultimately skepticism or nihilism.

The origins of relativism is all tangled up with what Christian Aristotelians of the Medieval Period were saying about the inherent pleasure of virtuous faith in God and with what was built on top of that by the philosophers of the Enlightenment period, who were so influential on the American Founding Fathers, with their famous “pursuit of happiness.”

Christianity was a strange and doleful religion. Life on Earth was a vale of tears. Only the next life has any real value. Noble minded Romans at first found it outrageously maudlin.

But Christianity was not entirely morose, or it wasn’t entirely morose for long. Aquinas and his fellow Christian Aristotelians and later the Renaissance Christian Epicureans in Italy characterized the heavenly reward of the faithful in the most sensuous terms, writes MacMahon.

For instance, Aquinas held that “In the final happiness every human desire will be fulfilled. MacMahon:

“Men and women will know perfect pleasure, the perfect delight of the senses. No pleasure would be lacking, even, Aquinas specified, (to the delight later of Nietzsche) the pleasure of enjoying others’ pain.”

Over time, even this life, the one on Earth, would be characterized as not lacking in pleasure, delight, and happiness. MacMahon:

“It has long been a truism of modern historiography that this shift from the happiness of heaven to the happiness of Earth was a product of the Enlightenment, the consequence of its assault on revealed religion and its own validation of secular pleasure. I would not dispute the main lines of this interpretation… but it is also the case that the shift toward happiness of Earth occurred within the Christian tradition as well as without.”

And:

“Creative speculation on the Christian meaning of happiness multiplied during the High Renaissance. In works like Lorenzo Valla’s On Pleasure (1431) and the monk Celso Maffei’s Pleasing Explanation of the Sensuous Pleasures of Paradise (1504), to name only two, little was left to the imagination, with accounts brimming over with the delights that awaited the faithful in the world to come. Classical descriptions of Elysium, the Blessed Isles, and the pagan Golden Age were freely adapted to give spice to the afterlife, as were Christians’ own accounts of the Paradise before the Fall, where, as Augustine had stressed, ‘true joy [had] flowed perpetually from God.’ The Renaissance imagination thus ranged freely forward to the joys that would come, and backward to those that had been. But the impulse to do so in such graphic detail clearly came from the present. The imagined pleasures beyond, that is, were a reflection of the greater acceptance of pleasure in the here and now.”

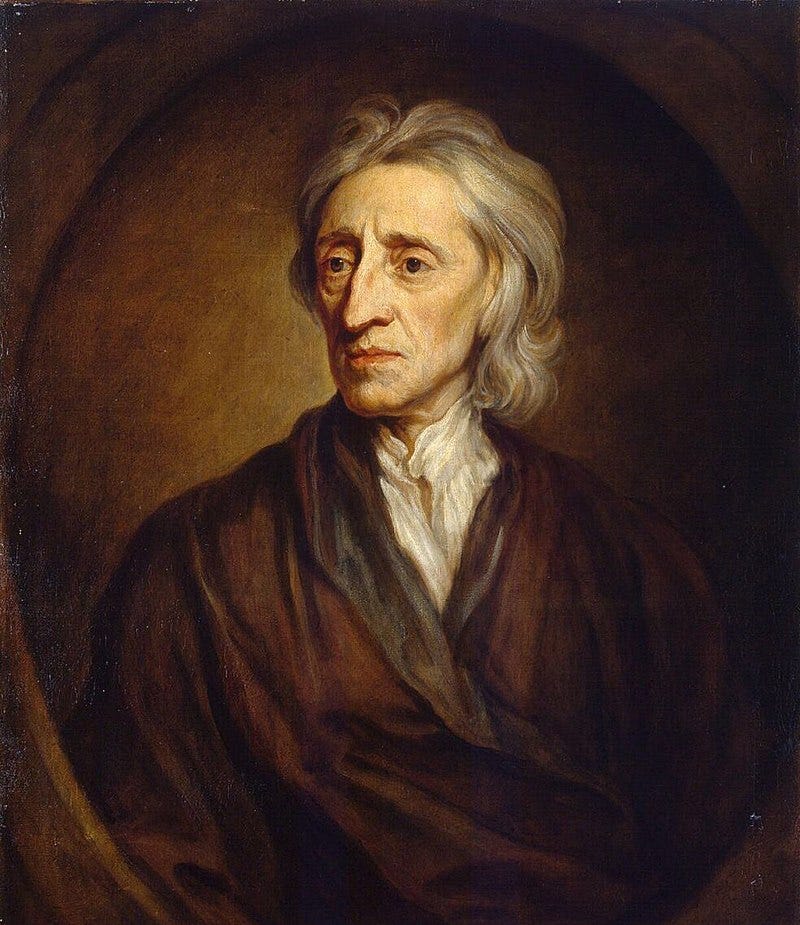

It is in John Locke that we finally get the complete and thorough conflation of the Good (value, virtue) with pleasure and with happiness, which, I’ll try to show, is the origin of relativism.

“In the famous chapter ‘Power’ in book 2 of [Locke’s Essay Concerning Human Understanding], Locke uses the phrase “the pursuit of happiness” no fewer than four times. And he employs a variety of Newtonian metaphors—stones that fall, tennis balls hit by racquets, and billiard balls struck by cues—to describe the ways in which human beings are propelled, and propel themselves, through the space of their lives. The force that moves them, we learn, the power that draws them near, is the desire for happiness, which acts through the gravitational push and pull of pleasure and pain. We are drawn by the one and repulsed by the other, and it is right that this is so. For in Locke’s divinely orchestrated universe, pleasure is providential; it is a foretaste of the goodness of a God who desires the happiness of his creatures.

So pleasure itself begins to be valorized as good almost in and of itself. MacMahon, quoting Locke, continues:

‘Pleasure in us,’ it follows, ‘is that we call good, and what is apt to produce pain in us, we call evil.’ And happiness in its full extent is simply ‘the utmost pleasure we are capable of.’

MacMahon glosses Locke thusly:

Here, then, was the monumental formulation. Redeeming pleasure, [this formulation] unabashedly coupled good feeling with the good.” [Whereas, remember, eudaimonia had started out as only about the fortune of being without misery, then it became about using the difficult practice of virtue to swamp tragedy, then pleasure sneaks in.-DF]

With Locke, there was pleasure in virtue and, but more remarkably, virtue in pleasure. Look around at our world today and ask what you can infer is the nature of what people think is good, worth aiming at, worth having? Why do we do what we do? What justifies our actions? That it feels good. It is good to seek pleasure. It is a virtue to seek pleasure. MacMahon, again found it remarkable that in Locke there is virtue in pleasure. MacMahon:

Arguably, there was no more widespread Enlightenment assumption. Moral sense theorists like Frances Hutcheson and Jean-Jacques Burlamaqui shared it, as did the Unitarian Joseph Priestly and the psychologist David Hartley. David Hume maintained as much, right alongside the French philosophers Helvétius and Condillac and the Italian legal theorist Cesare Beccaria.

Here are some formulations that are probably more familiar. Bentham:

“By the principle of utility is meant that principle which approves or disapproves of every action whatsoever, according to the tendency which it appears to have to augment or diminish the happiness of the party whose interest is in question.”

Thomas Jefferson:

“Happiness is the aim of life, but virtue is the foundation of happiness.”

Benjamin Franklin:

“Virtue and happiness are mother and daughter.”

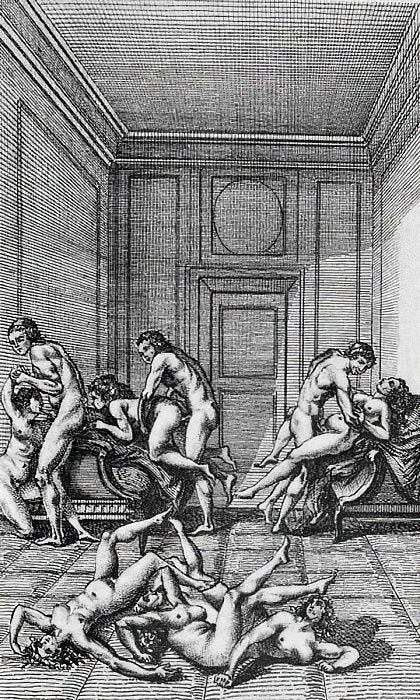

This conflation of The Good and pleasure or happiness was vulnerable to two contemporaneous attacks which its proponents often refused to see, MacMahon says. First, the proponents of the equivalence of pleasure and goodness/value, were hypocrites according to the likes of the Marquis de Sade and Julien Offray de La Mettrie, who both “pushed the logic of the pleasure/pain calculus to its ultimate [and untenable] extreme,” arguing that “if pleasure was good and pain was bad, then the most intense forms of pleasure—sexual or even criminal—should be embraced with virtuous gusto,” writes MacMahon.

“Sade and La Mettrie were written off as pariahs, decried as scandalous, condemned as immoral, accused of lacking virtue… But the assumption many fell back on to level this charge was not the century’s newly self-evident conception of happiness as utilitarian pleasure. They fell back instead on the teachings about happiness that had accumulated slowly over the centuries, amassed by Hebrew and Hellenes, classicists and Christians: that happiness and virtue, happiness and right action, happiness and godliness did indeed walk in step, but the journey was often difficult, demanding sacrifice, commitment, even pain.”

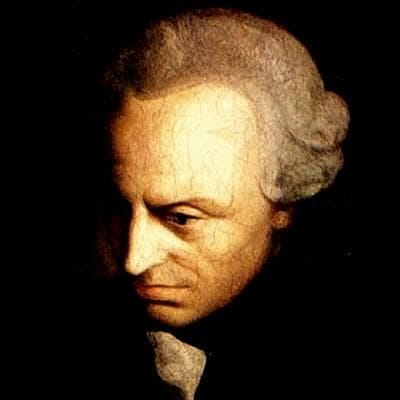

The second attack on the pair of ideas—that (1) doing good felt good and that (2) feeling good meant being good—was expressed by Immanuel Kant who said “making a man happy [was] quite different from making him good.”

“For if the proposition that doing good (living virtuously) meant feeling good (being happy) was always debatable, it was far more dubious still that feeling good meant being good. Virtue, Kant reaffirmed, with an air of common sense, was sometimes painful. And those who were happy, who felt good, were sometimes bad.”

This ought to have been obvious but many “eighteenth-century men and women were able to shield themselves from [this] uncomfortable truth,” this untoward consequence of their equation of pleasure and value.

“Why did not more people think through the implications and the logic of one of the century’s most dominant ethical impulses?”

asks MacMahon. His answer: They were…

“…simply not able to think through the implications of their increasingly contradictory assumptions about happiness—not able, that is, to see with the piercing vision of a Kant the contradictions that lay at the heart of the century’s newly self-evident truths.”

[Which reminds me of today’s illiberal retrograde leftism adopting many suspect ideas as self-evident and blasphemous to deny.]

Locke was one who did notice. But his solution involved, it seems to me, a logical fallacy, namely a vicious circle. As MacMahon writes:

“To his immense credit, John Locke understood this dilemma, saw with a perspicacity and foresight that rivaled Kant’s own the problems raised by the novel pursuits he set in motion. In the very chapter ‘Power’ of the Essay Concerning Human Understanding, Locke acknowledged, with more than a nod to his Calvinist past, that what prevented his system from devolving into a simple relativism [italics mine] of feeling was the prospect that one would judge the virtue of present pleasures and present pains—abstaining and acting accordingly—on the basis of future pleasures to come.”

In other words, the thing that stopped an adherent of “pleasure=value” from embracing the position of de Sade and La Mettrie was a wider scope for the utilitarian calculus, but not a redefinition of value in terms different in kind from pleasure.

As MacMahon points out, Locke tried to expand the wider scope of the calculus to include the rewards to come in heaven to those who avoid Sade-Mettrian dissipation in the here and now.

In The Reasonableness of Christianity, Locke wrote the following:

“Open [men’s] eyes upon the endless unspeakable joys of another life and their hearts will find something solid and powerful to move them. The view of heaven and hell will cast a slight upon the short pleasures and pains of this present state, and give attractions and encouragements to virtue, which reason and interest, and the care of ourselves, cannot but allow and prefer. Upon this foundation, and upon this only, morality stands firm.”

But how, I ask, was Locke planning on cashing out “interest” and “care” and “prefer” except as subjective pleasure? There is no other way for Locke and his fellows. And thus it remains possible that the otherwise immoral and even criminal pursuit of pleasure that de Sade advocated cannot be gainsaid.

MacMahon concludes the article from which I have been quoting (his 2004 introduction to a special issue of Daedalus devoted to happiness) by quoting from Locke’s Essay again:

“Were all the Concerns of Man terminated in this Life, then why one [person] followed Study and Knowledge, and another [person] Hawking and Hunting; why one chose Luxury and Debauchery, and another Sobriety and Riches,”

would simply be

“because their Happiness was placed in different things… For if there be no Prospect beyond the Grave, the inference is certainly right, Let us eat and drink, let us enjoy what we delight in, for tomorrow we shall die.”

If there is no God, there is no reason to do something unless it feels good to do it. Perhaps some of my readers and certainly many of my students would be satisfied if that were the upshot of Locke’s theory. But we must remember that God here in Locke’s theory is not some term above and beyond the utilitarian calculus equating pleasure with value. Locke is talking about God’s reward of pleasure to us in the afterlife for some unpleasant but virtuous actions we might engage in here on Earth.

If a de Sade and a La Mettrie calculations of their own subjective pleasures now vis-a-vis some pleasant reward later turn out differently, then Locke’s theory has no resources to rebut them.

There is no way around it, it seems to me: equating value with pleasure inaugurates a relativism of value which cannot be gainsaid until value is decoupled from pleasure.